I’m sitting opposite Saboteur’s coder, Clive Townsend, at a retro gaming show in the Midlands. Two pints separate us: beer for me, cider for him – ever the West Country boy – and Townsend is affable, smiling and jovial. “20 years ago, I could have reached across this table and rendered you unconscious in two seconds,” he grins. I laugh nervously while swigging a mouthful of Spanish lager. “But I’ve not trained for a long time. These days, I’d more likely breakdance a bit after a few drinks – but it usually ends in tears.”

Despite a career spanning 40 years, Townsend is best known for creating the 8-bit spy-ninja caper that we’re here to talk about today. “It was the 80s, so ninjas were everywhere,” he grins again. I do wish he’d stop doing that. “A mate and me used to watch loads of them, Jackie Chan and so on. I thought it would be cool to have a ninja running around doing a mission in a game. A sort of combination of James Bond, Batman and martial arts.”

Townsend grew up in 70s Somerset, the home of Ian Botham, cider and Cheddar Gorge, although it’s perhaps apt for this sleepy county that he remembers little of this time bar ‘climbing trees with my mates’. Then, as the 80s dawned, it wasn’t long before Townsend encountered home computers. “My introduction to computers was when a friend bought a ZX81,” he recalls. “Between us, we took turns reading and typing out the listings from magazines.” When typed into the computer, these pages of numbers and characters theoretically gave the user a playable game or utility. Unfortunately, just one missed character or – worse – a misprint, usually resulted in a non-working program. “We were often forced to examine the code and debug – perhaps without that, I would never have become intrigued by the behind-the-scenes of how the games worked.”

Having swerved the ZX81 for its successor, the ZX82, or, as it was to become known, the ZX Spectrum, Townsend’s first game was a simple Tarot card simulation. “It taught me loops and how to draw graphics – and its graphics were mostly monochrome, which turned out to be useful for ninja games.” Having coded a handful of minor games, Townsend took them to a local shop. “It was called Spectrum, so I thought they might be interested in computer games…” Curious and open to selling software, the camera shop nevertheless pointed Townsend toward an actual local games company: Durell Software.

Durell was founded in 1983 by Robert White, ostensibly to produce and sell insurance software. White himself had ambitions as a computer programmer but soon ceded to the talents of local coders Ron Jeffs and Mike Richardson, while noting the success of computer games. Its first games, Harrier Attack and Jungle Trouble, were hits, and by the time Townsend wandered in, Durell was up and running as a games software house. Having been promised a job upon leaving school, Townsend returned a few months later. His first task: to write a Spectrum version of an in-house game design. “Some magazines at the time said that my code for Saboteur was made from Death Pit,” notes Townsend. “But it wasn’t – although the concepts involved in making the game were.” Unfortunately for the teenage programmer, Durell deemed Death Pit unsuitable and canned the project, his work wasted. Well, not totally.

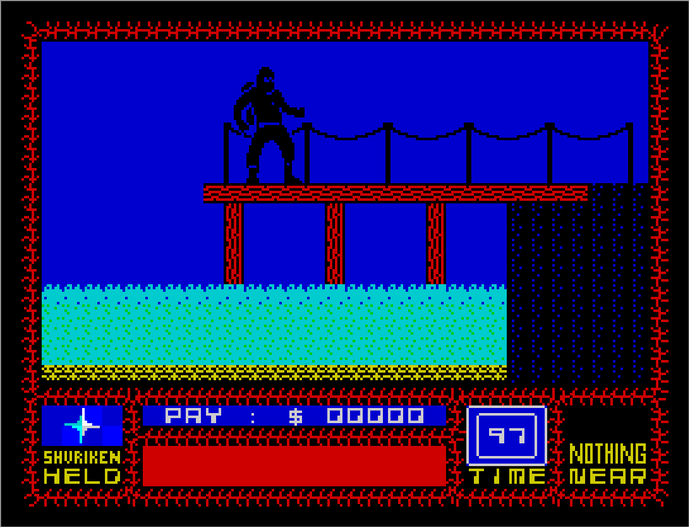

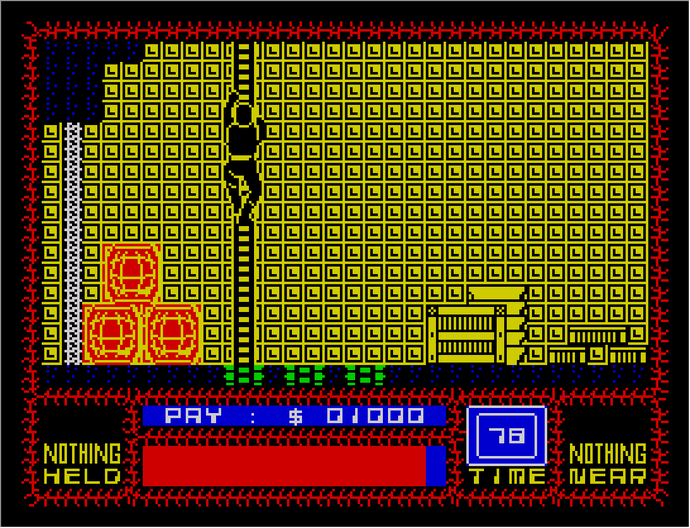

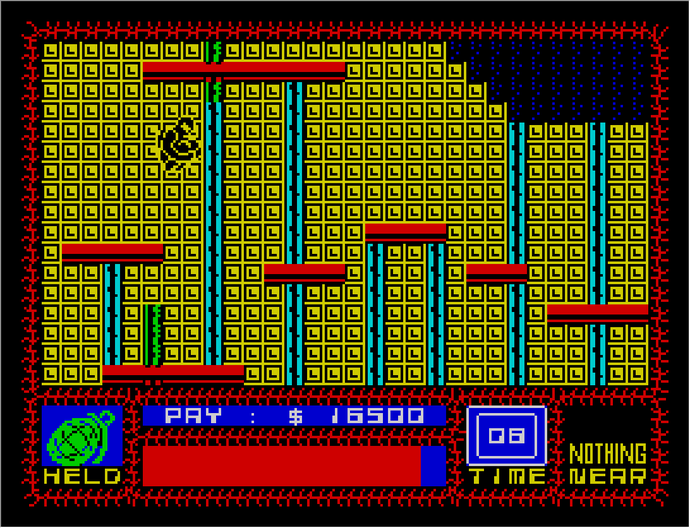

While working on the doomed Spectrum Death Pit, Townsend beavered away on another project in his spare time. “I did Judo and Karate as a kid, but each was a bit limited,” he says. “Then I discovered Ninjutsu, which seemed to combine other martial arts and also weapons training.” Townsend’s core idea was to send his ninja hero into a James Bond-style environment; before he had finished Death Pit, he showed his game, gloomily titled Ninja Darkness, to Robert White. “He said it was good – but the scrolling was too slow.” Still a relative newcomer to coding on the ZX Spectrum, this was a pixelated epiphany for Townsend. “He told me to make it flick screen instead. I suddenly realised that was a convenient way of solving the speed problem, as it only updated the bits I needed.” Now, Townsend could more efficiently arrange data such as his guard sprites – huge by the Spectrum standard of the time. “But they aren’t actually sprites!” he tells me “It’s a layer of background characters, then a layer of ninja characters, followed by a layer of guards and dogs.”

Big and imposing, Saboteur’s not-sprite guards made the game look impressive. But it wasn’t just Townsend’s graphics that set his game apart, especially on the 48K ZX Spectrum. “I had such plans!” he declares. “But everything costs memory, and there’s a limited budget. I knew roughly what I wanted [to put in the game], but couldn’t really judge how much space graphics, maps and music would take.” Nevertheless, in a market dominated by simple arcade clones and platform games, Townsend produced something quite remarkable for the time: a vast open world, with the player free to wander as they wish, complete with a regenerating energy counter, famously used by Bungie’s Halo series almost 20 years later. “It just seemed realistic to get your breath back if you stopped for a moment,” notes Townsend. “And while playing, I discovered that it created a nice trade-off between energy and time – do you waste time regaining your health, or keep running to save time, knowing one short fall could kill you?” A simple piece of code also allowed the player to utilise rudimentary stealth tactics, another novel concept for the era.

After almost 12 months of sometimes excruciating development (“I’d have the source code in memory, assemble a bit of code, save that to tape and then load in my graphics, data, and the bit of code I’d just made, test it, then load in my source code and assembler from tape, and process it all over again!”), Saboteur was ready, and quickly became a hit with ZX Spectrum owners in particular. The idea of a West Country teenage programmer working at a local software house and challenging the big boys of London, Manchester and Liverpool also appealed to the regional press and TV. “When Saboteur first came out, a TV crew turned up at Durell’s offices while I was asleep at home,” smiles Townsend. “They asked a load of questions about me and the game, and the last one was, ‘What’s next?'” Brimming with youthful enthusiasm and newfound stardom, Townsend’s reply was inevitable: “I said I think I’ll send the same ninja out on a different mission.”

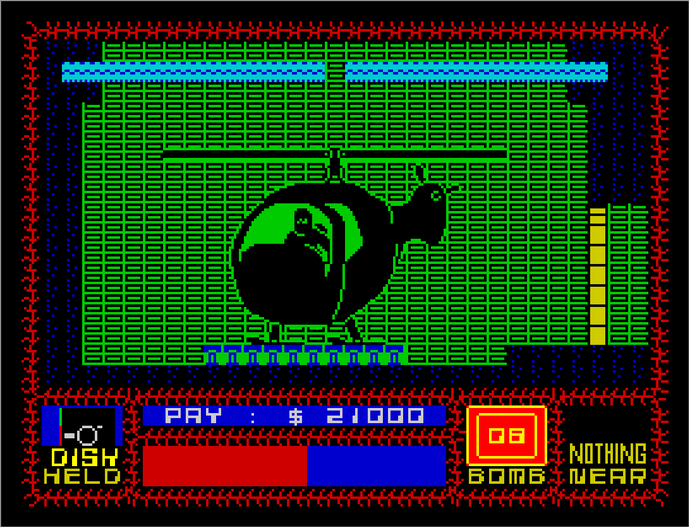

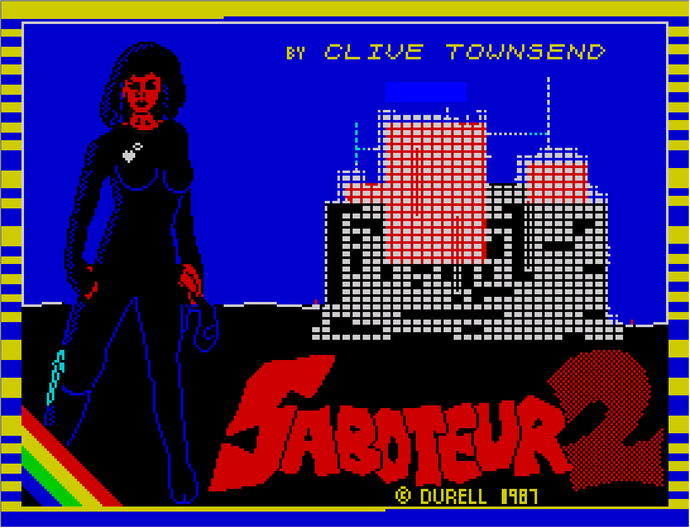

The sequel-shy Durell boss was perplexed, but Robert White gave his blessing nonetheless. Having excised several elements from Saboteur due to memory restrictions, Townsend began work on Saboteur 2, only for White’s wife, Veronica, to throw a shuriken in the works. “[Veronica] had asked why there weren’t more female characters in computer games,” explains Townsend. “I didn’t see how a female ninja would be less efficient than a male one, so we took a chance and hoped it would work. It was risky – this was way before Tomb Raider when suddenly everyone wanted female characters.”

With his engine and experience in place, Saboteur 2: Avenging Angel essentially presented more of the same – although its loading screen caused Townsend some headaches. “I copied my loading and title screens from pictures,” he says. “And I needed a picture of a leather-clad woman for Saboteur 2.” In these pre-internet days, such an image was difficult to find. Having used a picture from a ninja film poster for Saboteur, Townsend eventually found an equivalent for its sequel in an adult magazine, and the image becoming Saboteur 2’s impressive loading screen.

Sadly, despite the success of Townsend’s Saboteur series and games such as Turbo Esprit and Critical Mass, Durell reasoned that the games market was becoming too risky by 1987. The decision scuppered Townsend’s grandiose plans for a 16-bit Saboteur 3 and further sequels on PC and consoles. However, today, he’s busy updating his legendary 8-bit games for modern platforms (including the Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 5 and Spectrum Next) while also working on official follow-ups. It’s clear Saboteur’s popularity has not dimmed over the last (almost) 40 years. What does its author think is the secret to this enduring 8-bit legend? “I think it was because it treated its players like they were a bit older,” he muses. “The ninja phase of the 80s was also helpful, and I think people were similar to me in that they’d grown up on James Bond, spies and martial arts.”

I’ve been chatting to Townsend for almost two hours, and we’re three pints down – each. Fortunately, there’s no sign of any impending boogaloo, but I’m not pushing my luck, asking him one final question. Since the 80s, Townsend has worked on dozens of games over a range of platforms – but it was this period, working on Saboteur and its sequel, that he inevitably recalls most fondly. “I don’t think I realised how much fun it was back then, and I actually had money! I had no experience of work beyond working for an electrician for a few months in the summer holidays – aged 12! – so I’ve never had a real job. It’s been a strange life.”

For updates on the Saboteur series, go to Clive Townsend’s website. My thanks to Townsend for his time.